External Quality Control

Last week, I went off on a half-baked, thinking-out-loud, rant-ette on some of the snobbery around the use of CNC in guitar-making. I do have a couple of additional refinements to make on that subject but, for now, I want to continue down path I began.

Speaking of half-baked, I mentioned a phone call, with a friend, that had started me on this topic. Well, this friend is a guy that rings me every so often with a new plan to make me (he’s very generous) a million dollars… What if you build a guitar with an actual toaster in it? I mean, everyone loves toast, right? That’s the sort of thing. 😉

Something in that phone call really stuck in my head though. A concept we’ll call ‘external quality control’. That’s what got me started on this false CNC vs. handmade thing. What do I mean by external quality control? I’ll get to that. First, I need some more context here…

To summarise my argument from last time around, time, attention, and pride are the big differentiators; not whether someone’s hacked at the wood with a chisel.

It’s these qualities — time and attention (let’s assume pride is a given for the purposes of this discussion) — that make a guitar (or any product) something special. The more of these, the better the end result should be.

If I choose to build a guitar, I could spend every day of the next five years making it as perfect as my attention and pride allow.

But the reality is necessarily different. Realistically, I have constraints that mean it’s not possible to dedicate all of that time to one instrument. If I did, I’d have to charge five annual incomes for it. If someone’s willing to pay that, brilliant. But there are few people that can (or are willing to) pay that for a single guitar. Or I can hammer some nails into some lumber and string that up. It’ll happen much faster but it won’t necessarily be a world-class instrument.

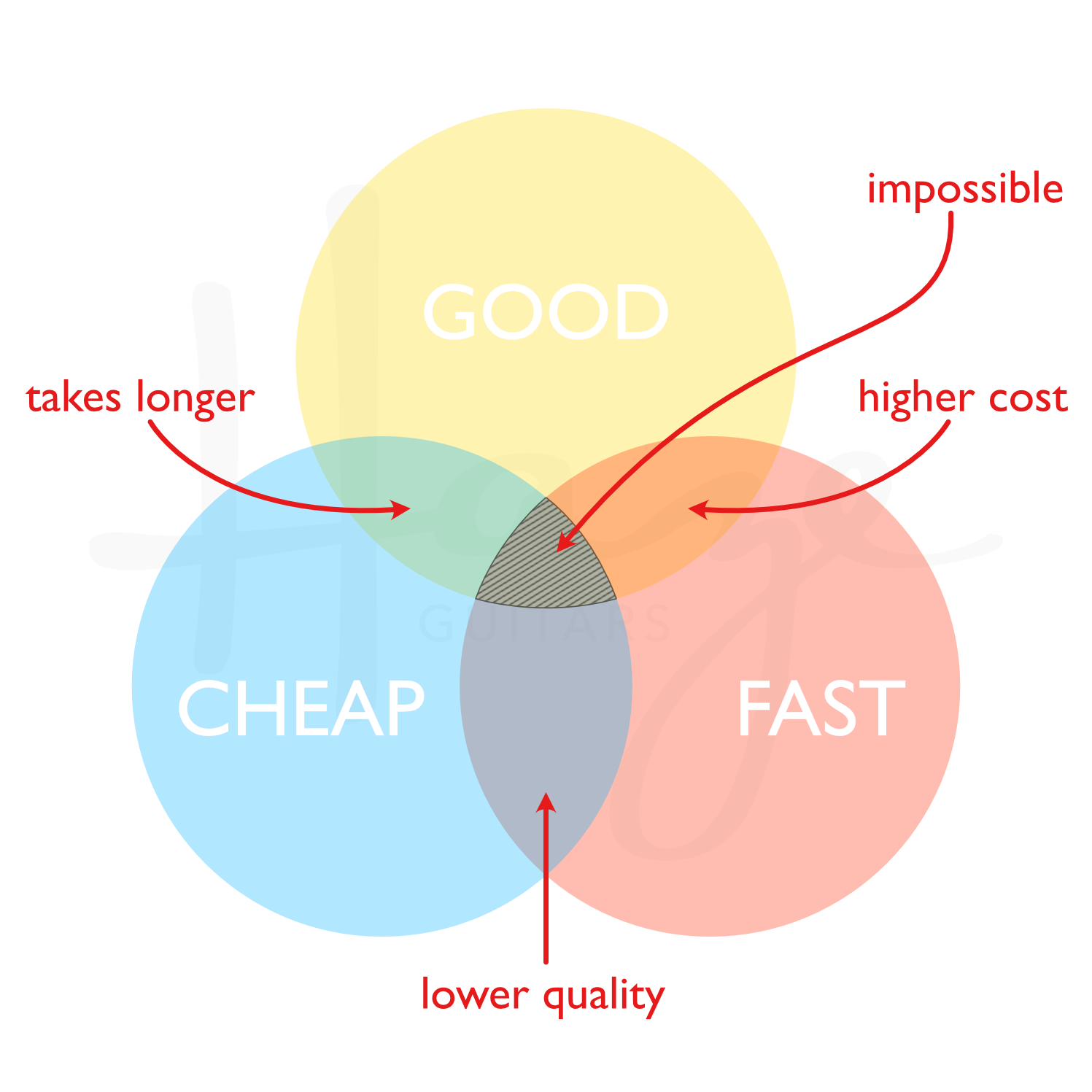

Let’s talk constraints. A concept known as the Project Management Triangle has become slightly modified over the years to become what most consider to be pretty much a law. It’s usually expressed as, ‘Good, Fast, or Cheap: You can pick only two.’

If you make something, you can decide to have it be higher quality and made very quickly, but you have to spend a lot of money to ensure these two things happen consistently. This means you have to sell your widget for more money to stay in business.

You can make it higher quality and cheap, but only if you sacrifice speed — your widget will take longer to make. Of course, this impacts how many you can sell and that brings its own constraint (getting back to my example of the five-year guitar, people have to pay the bills for that time).

But, before I stray too far into economics and the perils of capitalism (subjects I know nothing about), let’s get this back on the guitar track.

What would happen if we were all willing to pay $2000 for a Squier Strat? It’s probably safe to assume they’d be different instruments, right? If the team in the Squier factory could afford to give the guitar a lot more time and attention, the end result would likely be very different to the guitar that cost $200*.

For very sound reasons, some guitar companies have pushed their choices towards fast and cheap. And that’s absolutely valid and an incredibly good thing (guitar snobs are the worst). I do not want to suggest that Squier instruments aren’t ‘good’, partly because that’s not the case, and partly because this thing is a sort of spectrum anyway.

However, the realistic and rational among us recognise that instruments at the budget end of the spectrum necessitate some sort of compromise. If someone decides to choose fast and cheap as their desired features, the triangle tells us that the ‘good’ part must be impacted somewhat.

I’ve argued before (and will again) that how little the good actually gets impacted is extraordinary given the constraints these builders are working under. I find it incredible; the quality of an instrument costing a couple of hundred bucks these days.

But back to my pal’s ‘external quality control’ thing.

He reckons that it’s possible to go to the store and pick up a guitar costing very little. Then, to make up for some of the compromises it was necessary for the manufacturer to make, he can bring that guitar to someone like me. Someone he can pay to apply a little of the ‘time and attention’ that wasn’t possible back in the factory. A good setup, maybe a fret level, and he’s got a very playable instrument. Even considering the costs of this extra ‘external quality control’, his outlay won’t have been too substantial.

Now, I know that there are hundreds of people shouting, “but, the hardware!” at this, and you have a point. To an extent. Let’s leave that argument for a different day, though.

I admit that I’m weirdly taken with the external quality control concept. Conflicted too. The quality of budget guitars continues to get better and better and I don’t want to suggest a budget buyer has to bring their guitar to a tech. That said, I’m of the opinion that any guitar, no matter the cost, will benefit from a good setup with the actual owner in mind.

In trying to sum up all of this rambling, I’ll say it’s fantastic to be able to get guitars into the mitts of everybody, no matter their financial means. That these guitars can meet the standards they do, at their price points is amazing. And, if constraints mean they can’t all get the time and attention we’d like, we can choose to address any shortfalls after purchase, as time and funds permit.

Of course,

*We're ignoring hardware costs. Let's face it: That's not what makes up all (or even most) of the cost difference.

This article written by Gerry Hayes and first published at hazeguitars.com