More holes and countersinks

I want to pick up on something I mentioned in closing last time. I talked about slightly countersinking the finish at the top of a newly-drilled hole.

Two points on this:

First, I should have said that I just hand-hold the countersink bit to do this job. Some very light pressure and a couple of turns with my fingers doing the work is just fine. We're just trying to widen the finish around the hole slightly, not recess a screw head. Which brings me to my second point.

What the hell is countersinking?

Yeah, I should really have opened with that. Sorry.

Take a look at our screw again. There are different types of screws to do different jobs but the one we're concerned with here is the countersink-head screw. You can see the bottom of the head has a conical profile. If you cut a corresponding conical bevel around the top of a drilled hole, the screw can be inserted so it sits flush (or mostly flush in some cases) with the top of whatever surface it's in.

We typically use a countersink bit to get this done.

Countersink bits are available with different bevel angles but, we aren't doing precision engineering and a regular hardware store bit will do the trick for most jobs. The most obvious place you'll see countersinking on your guitar is on the pickguard. The screw holes have a countersunk bevel to accept the screw heads. Unscrew one to take a look if you've never noticed.

Common drill bits

The drill bit most people are familiar with is a twist drill bit. That's the one on top in the image below.

Twist drill bits in sizes above 3-4mm (around ⅛") will work for drilling wood but they can become more troublesome as they get larger. Twist bits can wander more easily and can sometimes 'grab' and pull suddenly. This can cause a bit to stray off course or, at worst, can yank out hunks of wood and finish that you'd much rather remained on the guitar. Larger sizes of twist bit really appreciate having one (or more) smaller pilot holes to guide them on their way.

Twist bits are good for cutting into metal and plastics. For wood, though, we can do better.

Brad-point bits (the one at the bottom in the image above) are specifically designed for cutting in wood. That sharp little point keeps the bit from wandering as you start and the leading edge cuts the wood as it goes rather than the more 'shearing' action of a twist bit.

If you get a set of brad-point bits, you'll see that the smallest sizes (below that 3-4mm I mentioned earlier) will actually be twist bits. That's fine in these small sizes.

For comparison, I've drilled two holes. The image on the left is using an 8mm brad-point bit and the one on the right is an 8mm twist bit. You can see the twist drill has given a more ragged edge while the brad-point bit made a cleaner hole.

Now, because this is a sharp twist bit, and because I proceeded quite carefully at a slow speed, the comparison isn't night and day. To better illustrate (and to warn you about this stuff), I used more speed and less care to get the image below.

Preventing tear-out when drilling

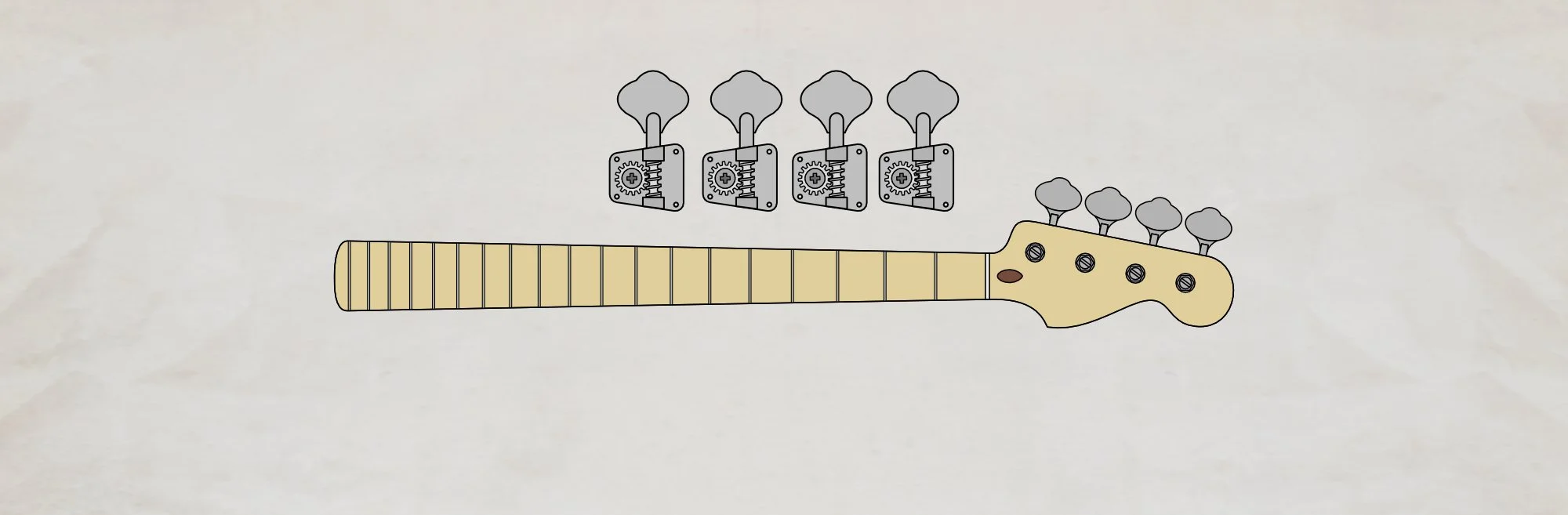

The raggedness shown above at the entry to a drilled hole is definitely something you want to avoid. Worse still, though, is the explosive tear-out that can occur at the drill bit's exit point.

This is a particularly nasty example that I forced for the purposes of illustration but it's not massively exaggerated. If you have to drill all the way through, you absolutely must take precautions against tear-out.

You can help prevent this by using sharp bits and by not rushing things. Pushing heavily on the drill as you go, in an effort to get through more quickly, will make tear out much worse. As you get close to the end, the pressure you're applying will burst through the last tiny section of wood instead of allowing it be cut by the bit. You don't want that so no rushing things and don't put all your weight on the drill. Let the bit do the cutting.

Even more importantly, use a backing board when you have to drill all the way through something. A backing board is just a sacrificial piece of wood that is pressed against the area where the drill bit will exit. As the drill cuts through, instead of bursting through, it just keeps cutting into the backing board. Splintering reduced massively. This is even more effective if you are able to clamp the backing board really firmly to the piece being drilled — less 'gap' between them to allow tear-out — but even the presence of a backing board will help a lot.

I'll just reiterate some important takeaways from all of this drilling stuff.

Pre-drill wood for screws to ensure accurate placement and to prevent split wood or broken screws.

Be aware of finish chips. Drill a little in reverse before your first hole. Consider a slight hand-countersinking of the finish layer around that hole to give the screw more clearance.

Let the drill do the work. You don't need to push really hard on it. If you're making really slow progress on a deeper hole, back out the bit to make sure the flutes (those helical grooves in the side) are not blocked with drilled material. Usually removing the bit from the hole will allow any swarf/material to fall clear and you can resume.

I'll just expand that last point a little. The difference between a good, sharp drill bit and a cheaper, or dull, bit is immense. Good bits can be more expensive, though. I realise this isn't something that everyone will consider a worthwhile investment and that's very fair. Remember to be even more careful if your bits aren't the fancy-pants expensive ones. Proceed more slowly and take more care.

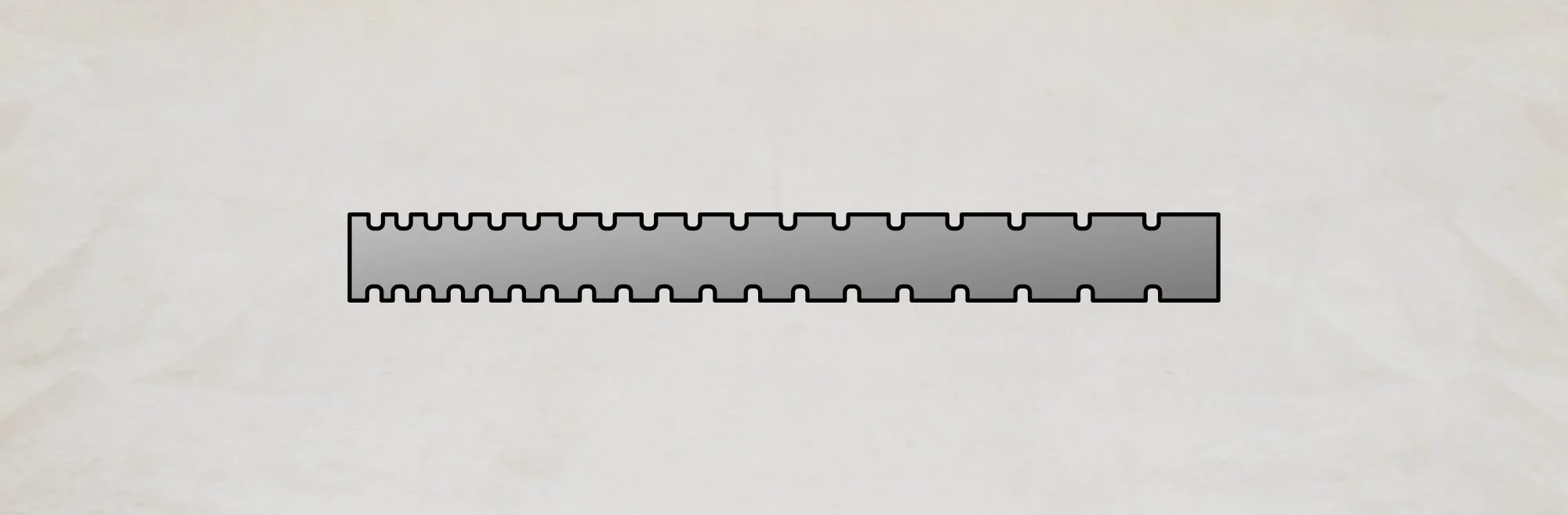

P.S. A little addendum on countersinking. In some circumstances, it's possible to use a larger size twist drill as a countersink. This needs care because it's easy to go that little bit too far and then the bit grabs and you've now got a big hole instead of a small countersunk hole. Sometimes, like below, there's no access for a countersink bit so a larger twist drill did the trick.

This article written by Gerry Hayes and first published at hazeguitars.com