The delicate tremolo balance

All this blocked tremolo talk is bringing us nicely to a drawback of a floating trem system: Shifting the balance can really upset the applecart (or banana-cart—stick with me).

So let’s look at that balance in a tremolo system and consider how it should work and what can go wrong. I’ll even throw yet more metaphors into this email as we go.

Consider a relatively standard guitar with a floating tremolo (one that’s free to move in both directions—raising and lowering pitch).

A standard set of D’Addario EXL110 10-46 strings has a combined tension of 102lbs. Let’s round that off to 100lbs for the sake of this example (I’m just sticking with pounds for this illustration).

My extensive research on Google tells me that an adult chimpanzee typically weighs between 70 and 130lbs. We’ll say, then, that the median chimpanzee weighs 100lbs.

Oh, yes… We’re going with chimps.

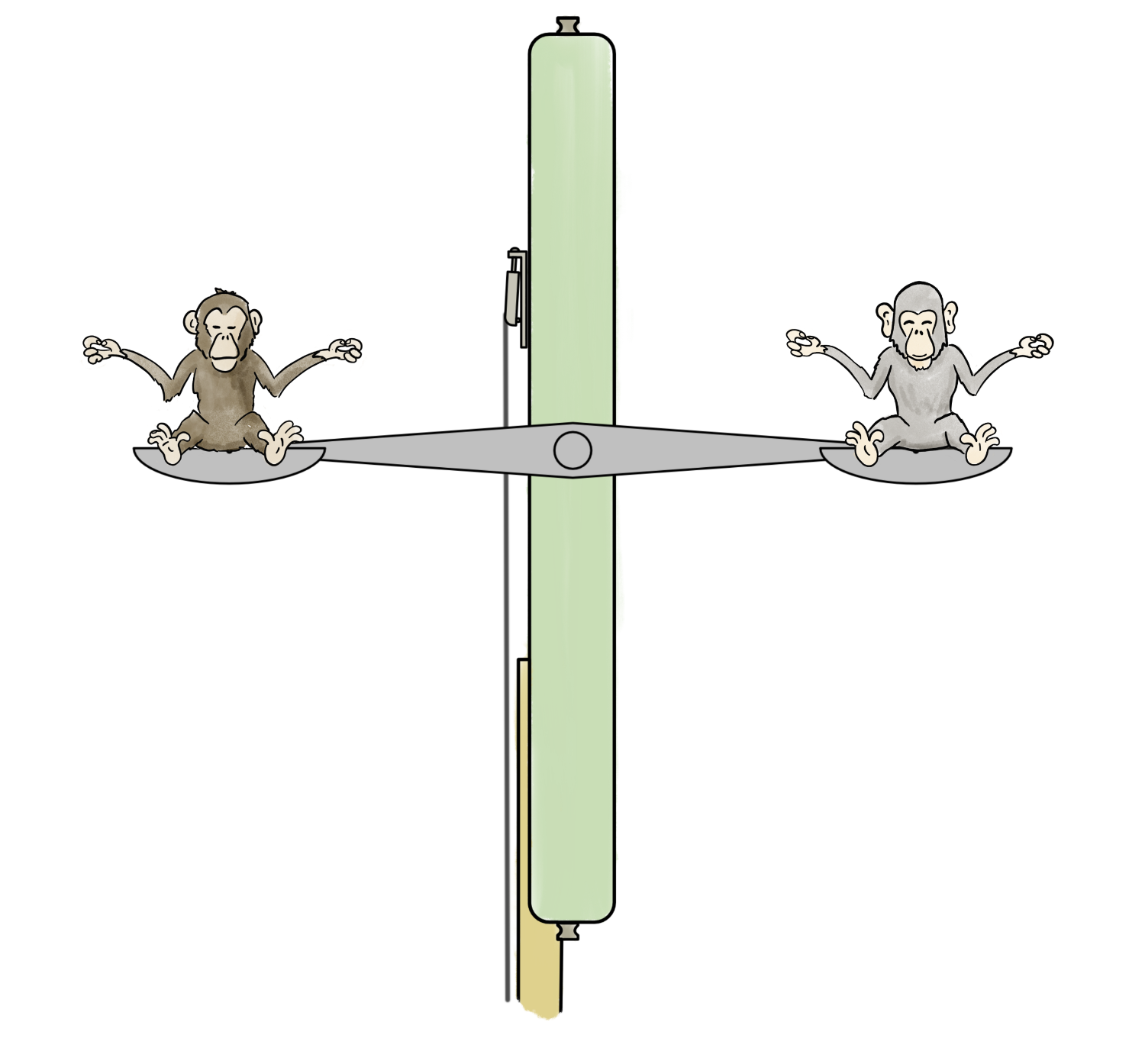

When you tune up the strings on your Strat, you’ve hung an adult chimpanzee from your bridge. Still with me? In order to prevent this mischievous primate from pulling your bridge all out of whack, we need another chimp around the back pulling the bridge in the opposite direction. So we have a 100lb chimp pulling the strings and another 100lb chimp pulling on the tremolo springs to counteract the first. The system (and the chimps) are in balance. All is well.

Now, imagine you’re playing a particularly moving blues solo and you bend your 1st string up a tone and a half. D’Addario’s tension chart tells me that going up a tone on this string increases its tension by around 6lbs (I’m simplifying things a little here). What you’ve just done is temporarily handed the string chimp a couple of decent-sized bunches of bananas. The scale tips in their direction.

Because the spring chimp around the back has no bananas to counteract the imbalance, he allows the bridge to tip a little in the direction of the strings. Tipping the bridge forward slackens all the strings (except the one being bent of course) so they go temporarily flat.

So, that string bend has inadvertently caused all the other strings to lower in pitch a little. Much of the time, you might not notice but if that’s a unison bend, the second (unbent) note will be a little flatter than you expect. Try a unison bend with an open string as your second note and you’ll really hear it.

Flutter can also be a problem in a perfectly balance system like this. Whack the strings with a pick and you cause them to vibrate. That vibration can pull on the tremolo springs too and introduce a little flutter into your note. And, of course, at some point most tremolo players will had an accidental string wobble from being a little heavy-handed with their palm muting (or even just resting the heel of their hand on the bridge). And that’s all nothing compared to the problems when you break a string. Or you want to drop your E to D.

All told, those chimps can cause a lot of trouble if we let them. Next time, we’ll start to look at some options to deal with with unruly chimps, who upset the delicate balance of things, and unruly humans who insist on using floating tremolos.

I’m sorry. I’m very sorry. 😄

This article written by Gerry Hayes and first published at hazeguitars.com