Heat-Treating Warped Necks

Last week, I began a conversation about ‘warped’ guitar necks. I talked about what they’re not and I was all set to talk about what a warped neck actually means but I hit a snag.

As I worked my way through my writing, I realised this was going to be a bigger topic than I could comfortably fit in one post. I also ended up with an ‘aside’ part that, while essential to the subject, didn’t really fit in the flow of the main discussion.

So, I’ve pulled that part out and will present it here. It might seem slightly ass-backwards to discuss a potential method to repair neck warps before actually examining neck warps but I think it makes more sense this way.

For that reason, I’m going to take a little look at attempting to correct a neck deformation by heating the neck.

Correcting warped necks with heat

There are two ways in which heating a guitar neck might resolve some deformation.

1: By ‘slipping’ the fingerboard glue joint

Heat can loosen the glue between the fingerboard and the neck itself. The neck is then forced into a ‘fixed’ shape and with some luck, when the glue re-cures, the new positions of board and neck will retain some of that fix.

This method comes with no guarantee of success and does have risks. However, not so many risks as the next method.

2: By ‘bending’ the entire neck

We can see, from acoustic guitar sides, that heating wood can make it pliable and capable of being bent to shape. If the wood is sufficiently heated, the lignin binding the cells and fibres becomes softened and, in theory, can be bent to correct a problem.

I say ‘in theory’ because this method involves a lot more heat. To avoid any remaining rigid sections that could split, the heat has to penetrate pretty thoroughly through the neck. This requirement for heat over a longer period brings increased risks. Consider that a neck is much thicker than an acoustic guitar side and you’ll get an appreciation of how much heat we’re likely to require to have a chance of a positive result.

Personally, I absolutely do not recommend trying this method.

How do you heat a neck?

Loosen the truss rod (if present) before you begin — you don't want to be fighting it or stressing it. I use a heating blanket. This is a heating element in a flexible sheath that covers the fingerboard. I’ll weight it down with some cauls or perhaps a levelling beam.

There’s a lot of checking of temperature (and quite a bit of guessing at heat penetration) involved and you should be familiar with the risks listed below. Keep feeling the back of the neck — this should never be more than ‘warm’. If it begins to get hotter to the touch, stop straight away.

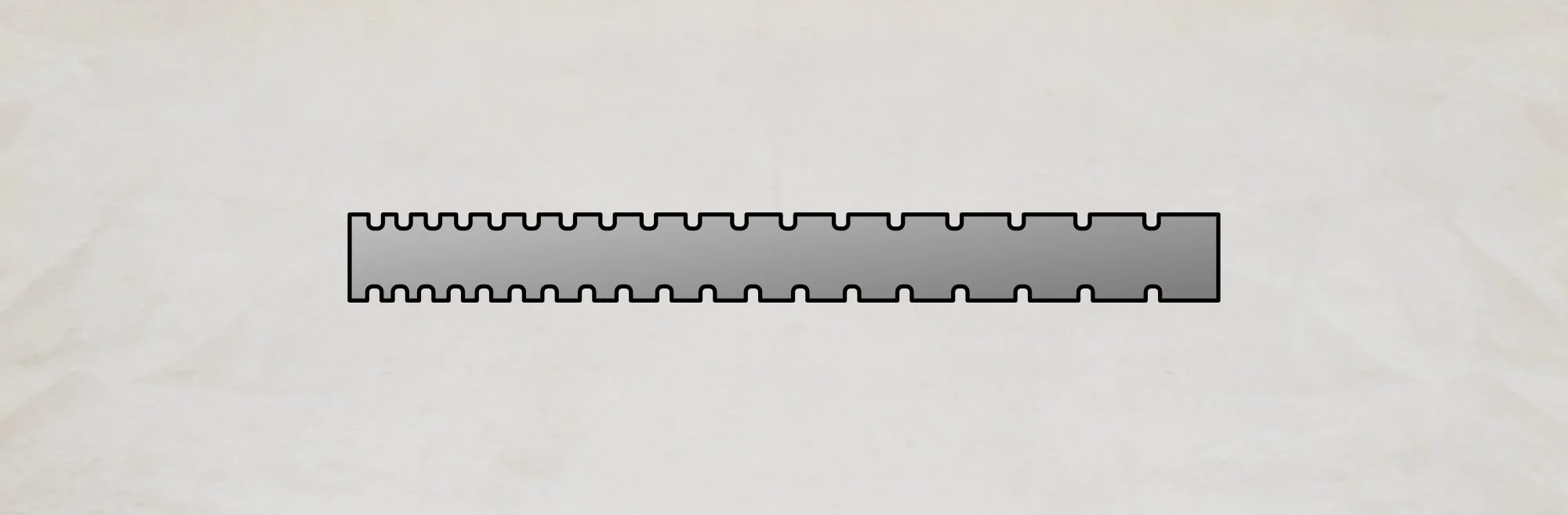

Once you feel your heat’s penetrated far enough and for long enough to soften the fingerboard glue, the neck can be clamped into a shape to correct whatever problem existed. Since you’re generally doing this to correct excessive up-bow or back-bow, this clamping will will typically involve a strong, rigid straight-edge along the neck with a spacer either end and a clamp in the middle. Check out the image below for an (exaggerated) illustration. Leave it clamped up for a day.

Instead of a heat blanket and clamped straight-edge, it used to be possible to get a device that combined both. This was a heavy metal (🤘) box that housed a heating element. It sat on the neck and provided heating but, because it was so rigid, it could also clamp the neck at the same time. Same principle with fewer steps and less ‘balancing’ of spacers and straight-edges. This tool was even called a Neck Straightener. I’ve never had one but one of my fellow, local repairers does and speaks highly of it.

What are the risks of heating necks?

If you have plastic inlays, you might be able to protect them with some layers of foil but there’s still a risk they’ll scorch, bubble, or burn and need to be replaced. Shell inlays won’t have this problem but may come loose as their glue lets go. Binding is usually plastic or celluloid and neither of these like heat. Frets may come loose and you should expect to check them for evenness after you’re done (and be prepared to resolve any issues). Oils in the fingerboard can bubble out and this means some clean-up afterwards and, of course, you should be stopping before the fingerboard actually scorches. And let’s consider lacquered fingerboards. Lacquer doesn’t get on well with excessive heat. Heating these is just asking for trouble.

That’s quite a list of hazards, I know but these things need to be considered.

With some protection of inlays and binding — and a lot of care — it’s generally possible to get fingerboard glue softened sufficiently to slip it without causing damage. But, be careful and be sure you trust your repairer.

Gerry’s bottom line

In my experience, the success of heat-treatment is limited. For minor deformations, it might work. And, for deformations that were caused by heat in the first place (say a neck bowing under tension as the guitar was left in a very hot location), it can be more successful.

I have had some luck with heat-treating neck issues but I’ve also found many that didn’t ‘take’ and many that worked their way back to being deformed over a period of time.

Heating a neck can be worth trying but be aware of the risks.

This article written by Gerry Hayes and first published at hazeguitars.com