More Making Holes in Guitars: How Deep to Drill

So, I learned an interesting lesson (or confirmed an interesting lesson): You can’t assume that everyone’s on the same page. Everyone doesn’t yet have the same skills and knowledge and you do them a disservice by assuming they do. I started last week’s post a little reticently because I was worried that talking about something like sizing a drill bit to a screw would be too basic. Turns out a heap of people appreciated it. I got a bundle of positive replies. Fantastic.

Let’s start with a little more screw-measuring.

How deep to drill a screw-hole

This one’s pretty easy. When pilot-drilling, you just want to drill for the length of the screw. Well, to be more precise, you want to drill for the part that will be in the wood. You can ignore the screw head for this job.

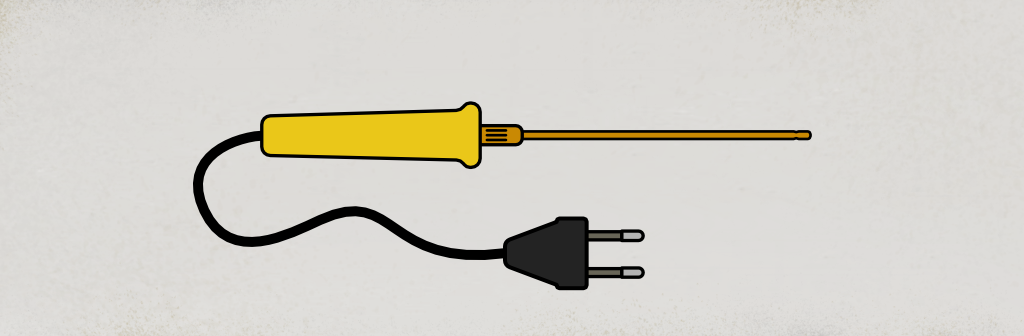

Offer your screw up to the drill bit again and assess the distance from the bottom of the screw-head to the tip. Use a Sharpie or (my preference) a piece of tape to mark this length on your drill bit. That’s your hole depth.

But not so fast.

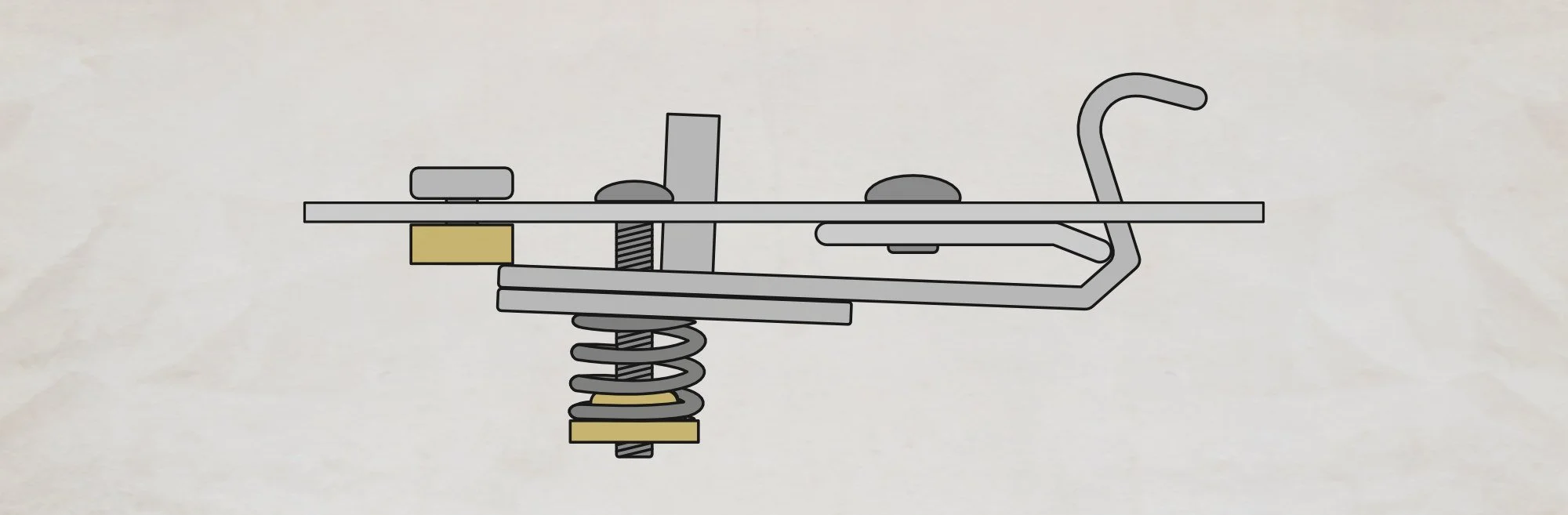

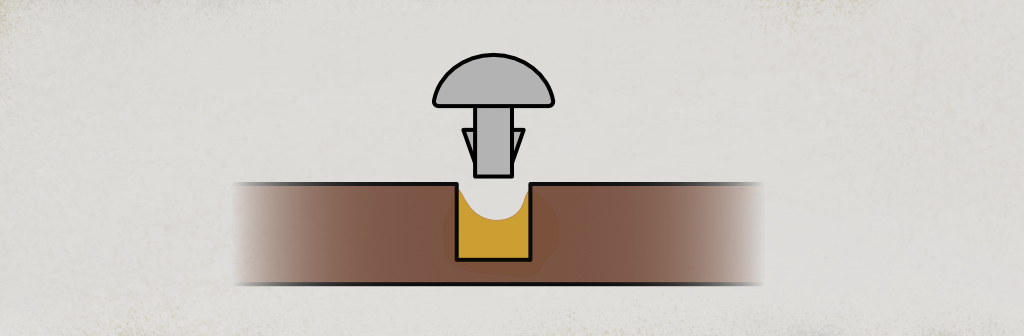

More often than not, when we drill a screw pilot hole in a guitar, the screw will be securing something to the instrument. Maybe a pickguard, a bridge, a cavity cover, tuner, etc. So, when drilling your hole, you can account for that part and subtract its thickness from your depth.

This stuff doesn’t have to be to super-tight tolerances or anything. A millimetre deeper or more shallow generally won’t make or break anything so don’t stress too much. You don’t need to use callipers to measure the pickguard thickness and a calculator to subtract it from your screw length but it’s good to get this stuff close. You don’t want to drill all the way through your guitar, after all.

That’s fairly unlikely if you’re installing a pickguard screw but, possibly, more of an issue if you’re drilling for a bridge screw. And remember: Sometimes guitars have cavities. What’s around the back from the location you’re drilling? Take a look before you start drilling, just to be safe.

Drilling into your guitar

First off, you need to know where to drill. Sounds obvious but, remember to line up or lay out your hardware accurately and then mark hole locations. I like to use a sharp scribe to mark the centre of the hole location. A scribe, with its small, precise, point, not only gives me an exact position, the little indentation it makes can act as a locator that helps keep my drill bit from wandering as I start.

If you don’t have a scribe or something that can give this accurate point, an option is to place a piece of low-tack masking tape on the location to be drilled and then use a sharp pencil to mark your hole locations.

Chances are you’re going to be using a hand-held drill. That’s fine for most DIY guitar jobs. A drill press is useful—and sometimes essential—for some tasks. When properly set-up, a drill press will cut perfectly vertical holes but, for most of this stuff, a standard drill will be fine. Just be aware of the angle you’re holding it and try to keep it perpendicular to whatever you’re drilling into. Again, making a hole for a pickguard or tuner doesn’t require an incredibly precise vertical hole but, if it skews too much, it can cause problems so keep things as perpendicular as possible.

Most guitars have a finish or some sort so you need to beware of lacquer chips as you go. Don’t go at this like it’s a competition to see how quickly you can drill through the guitar and the table its on. Start slowly and with only a little pressure. Almost all electric and cordless drills have a variable speed trigger these days so use that. Oh, and make sure your drill isn’t set to its ‘hammer action’ mode before you start.

It can be a really good idea to run the drill in reverse to start. That way, the bit will make a little ‘countersink’ to help locate itself. Also, it won’t want to ‘grab’ in reverse so it can be a little easier to control. This running in reverse can help protect the lacquer from chipping too. All in all, it’s a good idea. It just takes a second and you can switch to forward.

And when you do, remember, just a little pressure. Twist drill bit will often want to grab and pull as you go, especially if you push them too quickly. Be aware of this. Drill down to your depth marker and then remove the bit from the hole before releasing the trigger.

Hole done?

Almost. I like to protect the lacquer a little more. Remember that our pilot hole is smaller than the screw diameter. Even those screw threads can chip lacquer as they’re screwed in. I will usually countersink the top of the hole just a little. I’m not really widening the hole with this. I’m just trying to remove a little more finish so the screw can pass through more safely. I don’t want the screw trying to cut threads in the finish — just in the wood.

I just hand-hold the countersink bit to do this. I give it a couple of twists with light pressure and that's usually enough to add a little safety margin against lacquer chipping. If you don't have a countersink, you can accommodate the screw by just drilling a shallow hole (just the depth of the finish really) with a larger size drill bit.

A little more about countersinks next time. I’ll finish this drilling thing off then. For now, hit reply if you need to reply.

By the way, rather than sticking tape on a drill bit for a depth guide, you can buy bits with little depth stop sleeves. Stew Mac offers a set in common guitary sizes that I keep telling myself I’ll get to make life easier. Not that a piece of tape is particularly difficult but, you know what I mean.

This article written by Gerry Hayes and first published at hazeguitars.com